Colonial Sketches of Louisiana in Parisian Spaces

Unloading Goods from Louisiana on the Banks of the Seine by Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (Venice, 1675 - Venice, 1741)

THE SEARCH

My daughter and I were on a hunt. I had seen pictures of the painting we were searching for in Paris’ Petit Palais, and I was burning inside to see it in person. We asked all of the security guards we encountered where room 10 was, which is where the sketch resides, but no one seemed to know.

We scoured every inch of the museum in determined fervor. My daughter was a little exhausted but she hung in there because she knew it was important to me. In the very last exhibit…and almost giving up hope that it was on display; Low and behold, my pupils morphed into exclamation marks, there it was! “Unloading Goods from Louisiana on the Banks of the Seine” by Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (Venice, 1675 - Venice, 1741).

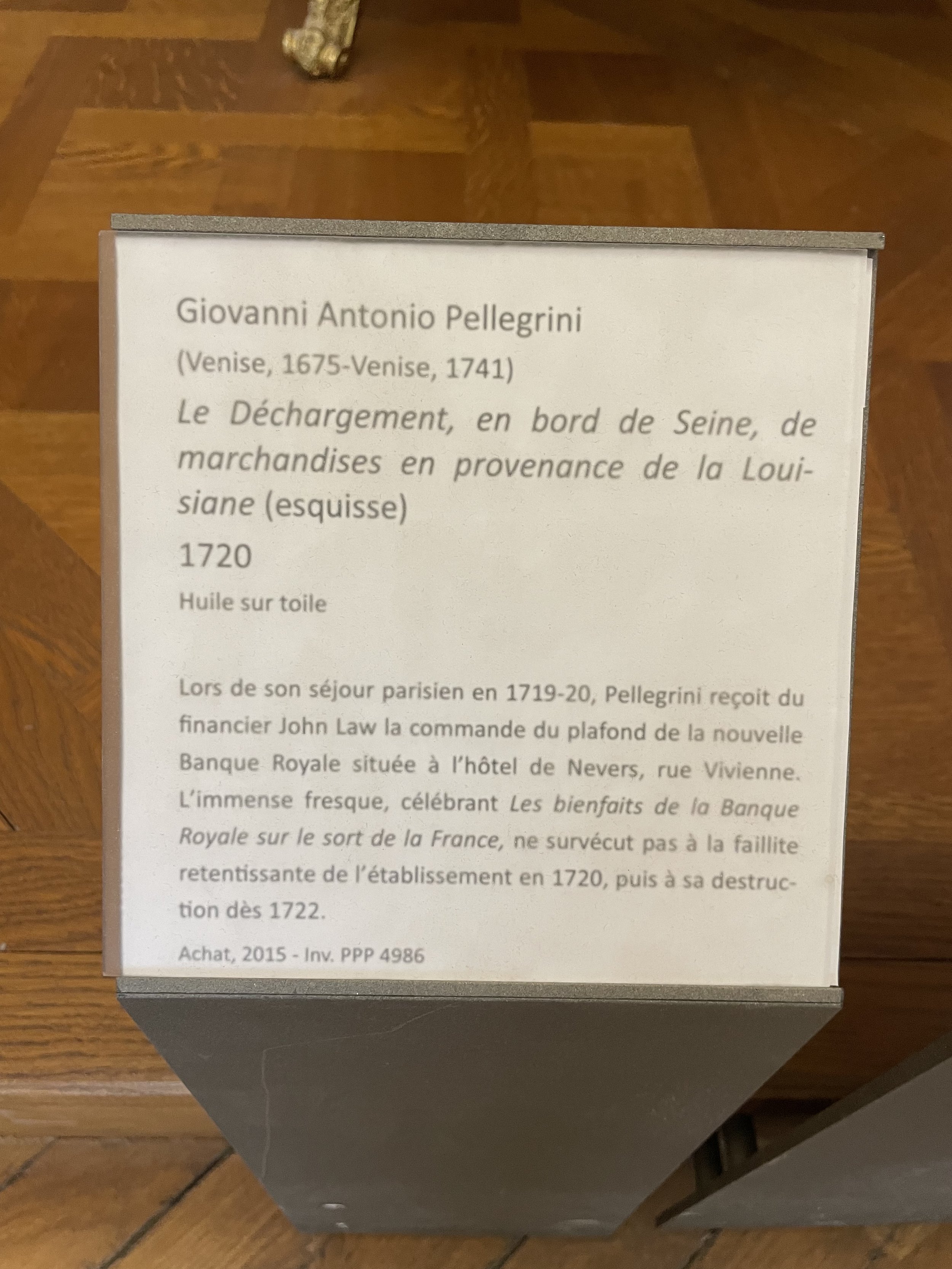

The museum label for the sketch in the Petit Palais.

English Translation:

Oil on Canvas

During his stay in Paris from 1719-1720, Pellegrini received a commission from banker John Law to paint the ceiling of the new Royal Bank located in the Hotel de Nevers, on rue Vivienne. The Immense Fresco, celebrating the fate of France and the benefits of the Bank Royale, did not survive the resounding bankruptcy of the bank in 1720. It was destroyed in 1722.

Purchase, 2015 - Inv. PPP 4986

Being a native of New Orleans and a student of our history, this sketch holds a lot of meaning to me. That’s right its a sketch. The 130 feet by 27 feet fresco that the sketch depicts was painted on the ceiling of the Royal Bank of France by Italian painter Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini at the commission of John Law in 1720. Not only is the sketch linked to Louisiana, it’s also linked to the founding of New Orleans in 1718 in particular.

THE UNDYNAMIC DUO

If you will, Louisiana was in it’s forth phase of French colonization. La Salle claimed it in 1682, Iberville and Bienville settled it in 1699, Antione Crozat was given private proprietorship of it in 1712 (more about that in this journal post), and in 1717 it was to become the Compagnie d’Occident (Company of the West). Five years into his charter and losing 1.2 million livres looking for silver and gold, Antione Crozat was exhausted with the exclusive 15 year concession he was given to develop the Louisiana colony. The death of Louis XIV on September 1, 1715 was his way out.

Louis XIV’s legitimate son was dead; his grandson, Philip V, was on the throne in Spain. His only heir was his five-year-old great-grandson, Louis XV. One can’t reign as king until he’s 13 years-old, so the plum of regent went to his nephew: Philippe II, Duc d’Orléans. Philippe was given to much debauchery. Franchine du Plessix Gray wrote that, “The Regency was the most dissolute period in French history and might well vie with the late Roman Empire as the most debauched era of Western civilization.” (At home with the Marquis de Sade: A life. pg.29.)

Orléans’ suppers became the subject of scandal, with orgiastic party’s rumored to be taking place nightly amid excessive drunkenness. Aside from working in his home chemistry lab and composing opera’s, one of the Duke’s hobbies included staying up all night with nobles, opera singers, and actresses who would all get drunk and sleep with each other. His contemporary Duc de Saint-Simon, reported that:

“As soon as supper-time arrived, the outer doors were bolted and barred so that, no matter what occurred, the Regent could not be disturbed. I do not mean for private or family matters only, but in case of danger to the State, or to his own life; and the incarceration lasted all night and well into the following morning. The Regent thus wasted an infinity of time with his family, his diversions, and his debauchery.” (Memoirs Duc De Saint-Simon Volume Three: 1715-1723. pg. 63)

It was Philippe II, Duc d’Orléans that commissioned the establishment of the capital of Louisiana. He gave Bienville, the governor of Louisiana at the time, two criteria: 1. He wanted the capital to be a port city 2. He wanted it to be named in his honor. Being the Duke of Orleans he wanted the city to be named La Nouvelle-Orléans (New Orleans). The city of New Orleans was named for him, and we’ve been trying to keep up with his lifestyle and nocturnal hours ever since.

Into this milieu came John Law, a Scottish banker who escaped prison in 1694 after being convicted and sentenced to death for killing a man in a duel over a woman. Possessing a mind like a calculator, Law built his wealth gambling and counting cards. While gambling in the Netherlands he studied the Bank of Amsterdam, Genoa, Venice and the fledging Bank of England. Law worked out a theory of banking, based on the idea that a banknote could change hands many times as fast as a transaction involving the physical transfer of gold or silver.

He spent years attempting to get one European kingdom after another to let him start a bank. After being rejected several times over he moves to a kingdom where the king is 5 years old, and who’s regent is more interested in gratifying his urges rather than managing an economy that’s in shambles from the War of Spanish Succession. Guest who the Duc d’Orléans is going to love?

A CHANCE ENCOUNTER

Law moves to Paris and starts networking, getting to know the right people, and after a night of gambling with some aristocrats he manages to stumble on a chance encounter…

The opponents Law swindled out of money invited him to a notorious house kept by a certain Madame Fillon. Madame Fillon was the foremost procuress in Paris and the cleverest at finding for her establishment girls who were well trained in the profession. When they arrived, the first person they saw was a little man wearing a black wig, surrounded by a group of tipsy young men and women.

One of the young men, dressed in ecclesiastical clothes, leaped over a table loaded with bottles. In a stuttering voice, the abbé, for such was his standing, pointed at the man in the black wig and began to lead those congregated in a chorus of the Joconde:

Cessez d'attaquer mon héros

Malheureuse cabale

Des gens qu'un indigne repos

Avilit et ravale.

Et quand vous parlerez de lui,

Du moins qu'il vous souvienne

Que Turin est l'oeuvre d'autrui

Et Léride la sienne!

The girls, shaking their heads, took up the chorus in plaintive voices:

Et Lérida la sienne!

Et Lérida la sienne!

The hero whom the song defended, smiled, even though he was numbed with wine and an indulgent, exquisite lightness. As Law looked at him he realised that he was face to face with the actual hero of Lérida that the song referred to the nephew of the King, His Royal Highness, the Duke of Orleans. Law made his most handsome bow and paid his respects to the prince in a few appropriate words. The Prince, slightly sobered by the noise, signed to him to sit down with the others, and at once ordered Guillaume Dubois, the abbé, to send for more wine.

Phillip had heard people speak about Law, and about his skill as a gambler. After talking the gambling circuits Law was famous for being in, Law began to share his ideas on finance. The explanations which followed gave the newcomer an opportunity to outline his projects, which he did with his customary eloquence. The Duke of Orleans was eloquent and he admired eloquence and bright, inquiring minds in others. Without delay His Royal Highness accorded Law an audience for the next day, and then called out for Du Bois, who at that moment was pirouetting around one of the girls, and told him to inform the secretary what he had decided to do.

The Duke of Orleans readily grasped all the points under discussion. The principle idea Law was putting forth was the idea to print paper money…and to him the ideas which the Scotsman put forward for converting all the State debts into paper money seemed most ingenious. Here was a man who on his own responsibility offered to create the bank with his own money. He proposed, in exchange for the privilege which he hoped to obtain from the king, to give over to His Majesty three quarters of the income earned by the enterprise. It wasn’t avarice that was prompting his action. His only desire was to endow the kingdom with a wonderful and useful scheme by means similar to those from which several nations were already drawing profits.

The Duke then advised him to take his project to the Controller-General of Finance, Monsieur Michel Chamillart, and he carried his kindness so far as to have a letter prepared for that minister which he gave to Law after he had graciously affixed his signature to it. His Royal Highness further informed him that, though, within the course of a few days he would be returning to the army, he had instructed Monsieur l'Abbé de Thésut to help him in every way during his absence.

Law was well satisfied with the results of his interview and went to Versailles to wait upon Monsieur Chamillart. The aspect of those impressive buildings at Versailles, marshaled magnificently, filled him with something more overwhelming than admiration. Law managed to convince the French to allow him to set up a private bank. Dreams of his own Versailles were within reach.

FROM THE GENERAL BANK TO THE ROYAL BANK

Eric Gabourel (the author) on Rue Quincampoix in Paris. This is the street where John Law lived and set up his Banque Générale

On May 20, 1716 Law was granted permission to establish France’s first banking institution. It’s called le Banque Générale, his privately owned General Bank. It’s a fancy name, but it’s run out of his house on Rue Quincampoix in Paris. On April 10, 1717, its banknotes began to be accepted as currency. He made the transition from being a “Rounder” on the card table to being an actual real banker. He prints paper money backed by gold and silver, but everybody thinks his bank is kind of a joke. That’s going to change as the Duke gives him more authority.

In his cozy home on Rue Quincampoix, Law developed a strategy to globalize his bank and pitched it to the Duke. In August 1717 Law convinced Orleans to create a monopoly on commerce with France’s largest overseas colony, Louisiana. The Compagnie d’Occident or Company of the West was created with John Law at the helm. Law vowed to make France for the first time a major power in maritime commerce and the equal of its English and Dutch rivals. He pledged that trade with Louisiana would save the country from looming financial disaster.

AN INTERNATIONAL CONGLOMERATE OF COLONIALISM

Instead of having one of John Law’s bank notes, I’m holding 10 Euros across the street from the site where the Royal Bank of France stood in the early 1720’s on Rue de Richelieu.

On December 4, 1718, at Law’s request the General Bank was nationalized and renamed Banque Royale, the Royal Bank. The Royal Bank was located in the Hôtel de Nevers on Rue de Richelieu. Most of the original Hôtel de Nevers was destroyed in 1859. The building was remodeled and extensively rebuilt and is now the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

The Royal Bank, under the control of John Law, was now a central bank overtly linked to the French monarchy. Ten days later, the Company of the West absorbed the Senegal Company, which had enjoyed a monopoly over the slave trade between West Africa and the French West Indies. The following January 10th, the Company of the West continued its expansion by incorporating the Ferme du Tabac or Tobacco Farm, the entity that regulated the sale of tobacco in France.

Both these mergers were crucial to Law’s dream of transforming Louisiana’s status as a colony by introducing a new commodity—tobacco—and the slave labor he considered essential for making tobacco profitable. When Law made tobacco central to his vision for the colony, realizing that enslaved Africans had become an essential part of the labor force in the Chesapeake Bay, he promised to send three thousand enslaved Africans to Louisiana.

Law then used his new powers to redirect the French slave trade, and on June 6, 1719, the first slave ships arrived in Louisiana. This one decision made on John Law’s authority had momentous consequences: it ultimately rewrote the destiny of this country’s second coast.

Law’s pitch to his principle financial backers focused on tobacco. To rope in small investors, he devised a very different marketing strategy: using newspapers to promote the territory as a new land of milk and honey. Because Law counted on the irresistible attraction for these shareholders of what he termed “the craving for profits,” he consistently stressed above all the colony’s potential for quick returns on every investment. Many prominent European papers were blatantly pro-Law, and none more so than the most widely read French periodical, the Parisian monthly Le Nouveau Mercure Galant.

The issue for March 1719 featured a letter from a Frenchman newly arrived in Louisiana sending news home for the first time. The account described the colony as “an enchanted land, where every seed one sows multiplies a hundredfold,” “a place laden with gold mines in the colony.” Gazettes also reported that a sample of Louisiana silver had been tested at the Paris Mint and found to have silver content even higher than that of the fabled Potosi mines in Bolivia that had been a foundation of Spanish colonial wealth…needless to say, the silver mines still haven’t been found.

Law’s promotion of Louisiana as a new source of fine tobacco and a new El Dorado proved so wildly successful that, within months, he had created the first known modern financial bubble.

In May 1719, an edict merged Law’s Company of the West and France’s largest trading company by far, the Indies Company. From then on, Law presided over the expanded Indies Company and controlled every aspect of the country’s overseas trade. On May 12 as the Royal Bank, shares in Law’s Indies Company, the first publicly traded stock in French history, were offered at 500 livers.

By October, Le Nouveau Mercure Galant informed its readers that anyone who had invested 10,000 livers in Indies Company stock in May had become “a millionaire.” For those who lived through fall 1719 in Paris, this first recorded use of the word “millionaire” conjured up a clear image: that of individuals, often “of humble birth,” who in a matter of months had become unimaginably wealthy.

Antoine Humblot, Rue Quinquempoix en l’année 1720, Londres, British Museum

During the Mississippi Bubble’s heyday, trading took place on the rue Quincampoix in Paris. This print, from The Great Mirror of Folly, is based on an engraving by Antoine Humblot commemorating the street as a hub of chaos, lust, and criminality, as well as of unprecedented social mixing. The Dutch version includes foreboding rope nooses, along with placards indicating various commercial schemes as well as the emotional states of those investing in them. At right, a man is apprehended by the police, even as he passes a purloined object to his companion; at center, a woman flirts with a man while appearing to steal his wallet. From a window at left, John Law himself eyes the mayhem. The chiming bell above announces a dealer’s intention to sell.

The worlds first millionaires were indebted to still another of Law’s creations: Paris’ first stock exchange. Prior to 1719, Paris had a currency exchange that operated for the benefit of the merchant with foreign exchange and foreign clients, but stock had never been publicly traded there. In August 1719, just as the price of stock in Law’s company was about to surge, an exchange for the commerce in Indies Company stock was inaugurated in his house situated at number 65 on the Rue Quincampoix.

FORCED DEPORTATIONS FROM FRANCE

In 1715 the Louisiana colony had only 215 French-speaking people in it, 160 of them soldiers.

Initially Law’s company sent ships with prisoners, falsely accused sex workers, money, wine, and supplies to the plantation economy. Law peddled land grants to 119 concessionaires as feudal lords with indentured servants and slaves shipped from West Africa. Law coaxed the duc d’Orleans to move denizens in French public hospitals to ships with beggars and inmates doing time for murders and debauchery. They also herded “prostitutes” from Paris’ La Salpetriere Hospital onto ships bound for the colony’s new capital, New Orleans. These weren’t the matrimonial candidates the governor of Louisiana, Bienville, envisioned to be sent to him.

In September 1719, as the abductions became known, 150 women at the port in La Rochelle started a riot to escape being deported to Louisiana. The guards shot six of them to death, and wounded a dozen more. The reminder were herded to La Rochelle, where they remained, ill clothed and ill fed, through a freezing winter that many did not survive. In January 1720, inmates at a French prison revolted, overpowering the guards and fleeing the prison, in terror of being sent to Louisiana. After the drag net had become so broad as to sweep up business visitors to Paris, Orleans put a stop to the forced emigration policy. But it had done its damage: there was little voluntary emigration from France to the Louisiana colony after that.

DELIVERING ON THE PROMISE OF 3,000 ENSLAVED WEST AFRICANS TO LOUISIANA

The principle purpose of the Company of the West’s absorption in the the Company of the Indies was organizing the slave trade to Louisiana. It held an exclusive trade monopoly in both Senegal and Louisiana during the years of the African slave trade to the latter colony. It’s port was Lorient, and almost all the slave-trade voyages to Louisiana originated from and returned to that port. Ties between Senegal and Louisiana were quite close. The Island of Gorée, near the present day city of Dakar, was the principle port in the Senegal concession. It was the main “Warehouse” of the slave “merchandise.”

While Senegambia became marginal to the growing African slave trade as a whole during the eighteenth century, its role in providing slaves for Louisiana was an exception. The West African’s were not referred to as slaves until they were sold in America: a legalistic fiction justifying their enslavement as captives of war.

The reason the Company of the Indies concentrated upon Senegal for the slave trade during the 1720’s is quite clear. The Senegal concession was the only place on the African coast where it held exclusive trading rights. Elsewhere, the company bought private permits to engage in the slave trade. Between 1726 and 1731, almost all the slave-trade voyages organized by the Company of the Indies went to Louisiana. Thirteen slave ships landed in Louisiana during these years. Over half the slaves brought to French Louisiana, 3,250 out of 5,987, arrived from Senegambia during this five years period.

The Mandinka kingdom was very prominent in Senegambia at the time. The Mandinga didn’t sell each other…they would capture the Wolof and sell them to the French. In fact, Le Page du Pratz, the director of the Company of the Indies in Louisiana, expressed preference for Wolofs.

During the 1720’s the Mandinka also captured and sold the Bambara people. The land of the Bambara, was located on the upper reaches of the Senegal River beyond Galam, near the Niger River. Bambara slaves were brought to Louisiana in large numbers and played a preponderant role in the formation of the colony’s Afro-Creole culture.

Both Mandinga and Bambara were Mande peoples claiming descent from the Mali empire established by Sundiatta during the thirteenth century, but there were strong religious differences between them. While the Mandinga were proselytizers of Islam, the struggle against Islam was an important component of Bambara identity until the late nineteenth century. This is one of the reasons that the Mandinga concentrated upon capturing and selling them.

Between 1719 and 1723, ten slave ships landed 2,083 enslaved West African’s in Louisiana.

THE FIRST SLAVES ARRIVE IN LOUISIANA

Though Bienveille (the founder of New Orleans) and the French settlers in Louisiana wanted West African slaves since settling, the first record of enslaved West Africans coming to Louisiana was in 1709. Bienville sent the ship, la Vierge du Grace, to Havana under the pretext of looking for powder, and embarked several slaves. By 1712, there were only 10 West Africans in all of Louisiana. By 1721, the year that the Company of the West went into decline, seven slave ships arrived to Louisiana counting 680 West African’s according to the census of November 24, 1721. The census reported that Bienville owned 27 of them.

While the Company of the West was in control of Louisiana almost all of the West African slaves brought to French Louisiana came directly from Africa and arrived within about a decade. Only one African slave trade ship came to Louisiana after 1731: a privately financed ship that arrived from Senegal in 1743.

Between June 1719 and January 1731 sixteen slave-trading ships arrived in Louisiana from the Senegal concession of the Company of the Indies. During the same period, six came from Juda (Whydah in present day Benin) and one from Cabinda (Angola, Central Africa). Five out of the six ships from Juda and the lone ship from Angola had arrived by June 1721.

Fiche de Desarmement of the first two African slave-trade ships, Grand Duc Dumaine and l’Aurore, to Louisiana, dated October 4, 1719

Although the Company of the Indies made early, sustained efforts to supply Louisiana with slaves from its Senegal concession, most of the early voyages went to Juda. The first two voyages were organized by the Company of the West before it was incorporated into the Company of the Indies. L’Aurore and le Duc du Maine left St. Malo together during the summer of 1718 and picked up their “cargo” at Juda.

The captains were instructed to try to purchase several West African’s who knew how to cultivate rice and three or four barrels of rice for seeding, which they were to give to the directors of the company upon their arrival in Louisiana. Subsequently, rice became an important food staple in French Louisiana and was at times exported.

l’Aurore arrived at Juda on October 18, 1718 (the year New Orleans was founded). There were English, Dutch, and Portuguese slave ships in the harbor. There was stiff competition to buy slaves at the time. In 1721, the Portuguese built the fortress of Whydah, consolidating their predominance at the Gulf of Benin.

l’Aurore left Juda on November 30, 1718, with 201 slaves, half the number the company expected her to carry. The voyage from Juda to Louisiana took about six months. When these ships arrived they docked up on Dauphin Island. Many of these slaves were reportedly lost when the Spanish took Pensacola. le Duc du Maine, landed 250 in Louisiana.

During 1720 and 1721, three voyages organized by the new Company of the Indies picked up “cargo” for Louisiana from Juda, despite the severe shortage of “merchandise” there. L’Afriquain landed 182 enslaved people, and le Duc du Maine, on its second voyage to Louisiana, landed 349. Both ships arrived in March, 1721.

As soon as the Company of the Indies took control of Louisiana, it devoted serious attention to supplying the colony with slaves from the Senegal concession. Le Ruby was the first slave-trade ship that arrived in Louisiana from the Senegal Concession. It left Le Havre in December 1719 and Gorée in May 1720 with 130 slaves, arriving in Louisiana in July, 1720 with 127 slaves.

Between November 1720 and September 1721 the Company of the Indies sent several ships to Senegal to bring slaves to Louisiana. Le Maréchal d’Estrées left Le Havre for Senegal on December 15, 1720 landing 196 slaves in Louisiana.

RESISTENCE

Of course the people being trafficked tried to resist their sale and forced migration. This resulted in several casualties that occurred during transport and the “merchandise” did not always die quietly. On October 18, 1724 at four o’clock in the afternoon, the 55 captifs stored in the captiverie at Gorée were in the courtyard, where they were normally brought for fresh air. They revolted, armed themselves with pieces of wood and with several knives, and stabbed the French storehouse guard.

They removed their shackles with two axes they found. Hearing the screams of the warehouse guard, the rest of the French came running to help him, but it was too late. He was found all bloody, his intestines cut and hanging out of the would. He died the next day. The French fired on the captifs, killing 2 and wounding 12. The captifs took refuge inside the captiverie and remained on alert all night, making fires in the courtyard and on the ramparts. At eight o’clock the next morning, they informed the caitifs that if they did not surrender, they would be burned alive. The caitiffs asked the French to open the doors, which they did at once. They made the captiffs come out two by two, followed by three guards. After all of the rebels were brought out the French found out who the leaders of the revolt were, tied one of them on two pieces of wood and cut him in four quarters, and shot 2 others, to serve as an example.

Documents in France, from Senegal, and from Louisiana all recognize that the long stay in the captiveries was the principal cause for high mortality at sea and after landing. A steady stream of captifs filled the captiveries while the Company of the Indies struggled to refit its ships in Lorient and send them back quickly to Senegal to load them. The captiffs died en masse in the captiveries, and the survivors were so weakened that many of them died aboard ship. The loss in transit on most of the slave ships landing after 1726 was devastating. Of the 11 recorded journeys of French slave-ships to Louisiana between 1726-1731 it was recorded that 4,098 enslaved people were boarded, but 645 died at sea in transit to the Louisiana coast.

When these ships arrived in Louisiana, they had to enter the Mississippi River at Balize in the face of contrary winds and tides and ever-shifting sandbars that blocked the channels. Sick and dying, exhausted, short of food and water, often without clothing even in midwinter, the captifs waited for days for flatboats and pirogues to take them up the Mississippi River to New Orleans, where they often encountered food shortages. Many of them died on their way to New Orleans or shortly after their arrival. Documented illnesses included scurvy, dysentery, and an inflammation of the eyes. They were kept naked on the ships even in winter for sanitary and security reasons.

The Bambara, arriving in Louisiana in large numbers after 1726, first encountered Native Americans as their fellow slaves. The first slaves in French Louisiana, held from the earliest years of colonization, were Native Americans. The French bought, sold, and even exported Native American captives from Louisiana to the French West Indies.

After New Orleans was founded, escaped Native American slaves remained in and around the city, killing and eating cattle belonging to the settlers. As increasing numbers of Africans arrived during the 1720’s, African and Native American slaves, sometimes owned by the same masters and sharing the same fate, ran off together, stealing food, supplies, arms, and ammunition from their masters. They often were well armed and raided the settlers for more supplies.

The image depicted in the fresco that John Law commissioned Pellegrini to paint on the ceiling of the Royal Bank was as preposterous as the propaganda he was printing in Le Nouveau Mercure Galant.

THE ART

In 1920, just before the Mississippi Bubble was about to burst, John Law commissioned the fresco on the ceiling on the Royal Bank. To the great dismay of his French rivals. Gianantonio Pellegrini, admired throughout Europe for his virtuosity and the lightness of colors, received the commission to paint the ceiling of the boardroom in the new Banque Royale.

Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (29 April 1675 – 2 November 1741) was one of the leading Venetian history painters of the early 18th century. His style melded both Renaissance and Baroque styles of painting. Baroque artist typically painted pictures that captured the ultimate dramatic moments that showed unfolding events taking place in real time. You were no longer left to imagine what took place. These scenes were being depicted in realistic detail, they were theatrical snapshots if you will. Baroque art would also portray mythological events. Divinity in the clouds would be used as a medium to tell part of the story. The idea was to evoke a spiritual response without making it overtly evident.

Pellegrini got to work portraying the ideas of John Law’s hypothetical revenues from the Louisiana colony. The sketch of the fresco that survived shows a large section of the composition. To the left of the painting is a ship that just arrived in Paris from Louisiana. The deckhands and stevedores are seen working in unison loading goods unto a cart drawn by two horses. The contents of the sacks are left up to the imagination of the viewer. But in the mind of the inhabitants of Paris it represented either sugar or tobacco. The work of the deckhands and stevedores portray the meeting of the Mississippi River and the Seine River…the benefits of colony to metropole.

On the right, two women can bee seen in angelic light assisting a man that seems to be inflicted with misery…be that homelessness, injury, or illness. The scene speaks to the illusion that the Company of West existed to lift France’s crippled economy out of poverty. That by investing in the company you could become a "millionaire.” The existence of the Royal Bank and the Company of the West is the platform for which prosperity was to be ushered into the French Economy. It would come at a cost.

In the clouds above the scene to Louisiana’s bounty being offloaded in Paris are the winged allegories of Felicity and Tranquillity. These angelic beings represent the prosperity that the Company of the West is to usher into the French economy. The allegories portray peace, happiness, financial security, prosperity, and more importantly God’s providence over this organized implementation of manifest destiny.

But on the ground in Louisiana the real picture was grim. The forced migration of French prisoners and sex workers to New Orleans. The confiscation of Native American land to grow sugar, rice, indigo, and tobacco. People being kidnapped and trafficked to the Louisiana colony from Senegal, Gambia, and Mali. The misery of those from the other side of the Atlantic persisting in the swampy, subtropical environment of Southern Louisiana.

Rather than angelic figures of Felicity and Tranquility in the clouds, the sky over Louisiana was an abysmal night submerged in misery. The death of the prisoners who dug the ditches to create the street grid for New Orleans. The death by Yellow Fever of the engineer, Adrien de Pauger, who designed the street grid. The lives of those crammed in the bottom of ships and forced to come to Louisiana that were lost while crossing the Atlantic. The crippled free will of the enslaved whose sole destiny was to toil in the humidity of the plantations. The land confiscated from the Native American’s and their displacement. This was the cost of production for the prosperity of the Company of the West and its investors.

The false narrative of the Company of the West would come to an end. The financial speculations of the Company resulted in the Mississippi Bubble. John Law and Phillip II’s Ponzi scheme crumbled, and with it the destruction of Pellegrini’s painting on the ceiling of the Hotel de Nevers. Regardless of the paintings destruction, the underpinning that the company started would never come to a halt. A legacy of colonialism and its offspring Neo-colonialism were established and would become the status quo.

The names and identities of the West African’s would be changed. Their status as humans were changed from people to possessions. They would be given the last name of the owner of the plantation they were purchased to labor and live on. The prevailing ideas and customs of Louisiana found the slavery of West African’s legitimate, and that among those of European decent, some of them were born to command, others to obey.

The Native American’s who were welcoming of the French settlers would soon awaken to their lands being slowly taken. In 1729 escaped slaves and the Natchez people, lead by supreme chief Great Sun, would soon organize a revolt against the French settlers in Natchez in what’s now the state of Mississippi. The resistance effort led to the deaths of more than two hundred French settlers and soldiers. Such efforts didn’t slow down or stop colonization…in this case the empire beat the rebellion. The Natchez were obliterated and those that weren’t killed were forced into slavery in St. Domingue.

The collapse of the Royal Bank in 1720 and the destruction of the fresco in 1722 to erase the memory of the debacle of the Mississippi Bubble actually gives us a sense of hope. In 1722 there was a 28 year old Voltaire stirring the political pot with his Enlightenment ideas. He was sentenced to prison twice, exiled to England, and spent an 11 month stent in the Bastille for critiquing Philip II. There was also a young Jean-Jacques Rousseau developing his Enlightenment ideals that would be praised as influences of the French Revolution. Some of his central ideas can be found in his Discourse on Inequality and The Social Contract.

Such ideas lead to the development of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and the overthrow of King Louis XVI. This declaration also lead to the development of “The Black Jacobin’s” in St. Domingue and the Haitian Revolution. This document also influenced the Pointe Coupée slave uprising here in Louisiana in 1795.

Not only would a fresco on the ceiling of a bank be destroyed, the French Revolution in France and the Haitian Revolution in St. Domingue overturned entire socio-economic systems. In Louisiana however, the efforts of Samba Bambara conspiracy of 1731, Juan San Malo’s Marron’s in the 1780’s, the Pointe Coupée slave uprising of 1795, the German Coast uprising of 1811 would all be suppressed. Liberation wouldn’t begin to come to bare until the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863…and the struggle for a more pure democratic distribution of wealth continues.

While we reflect on the roll John Law played in the history of finance, it’s important to remember that at the time the people of France called for his head. On December 17, 1721 Law secretly fled France for Brussels on an escape plan devised by the Duc de Bourbon. The Third Estate was at a tipping point.

The Kingdom of France, when New Orleans was founded, was organized under the Ancien Régime (Old Regime) which consisted of the three estates. The clergy and the nobles, which constituted 2% of the population, made up the first and second estates. The third estate (98% of the population) consisted of the peasants or common people. The urban dwellers of the third estate included wage-laborers. The rural population of the third estate included free peasants (who owned their own land) and villeins (serfs, or peasants working on a noble's land). The Third Estate paid disproportionately higher taxes compared to the other Estates and were unhappy because they wanted more rights. The First and Second Estates relied on the labor of the Third, which made the latter's inferior status all the more glaring. It was the third estate (the 98%) that would overthrow the monarchy and the first and second estates (the Old Regime) during the French Revolution.

The power dynamics created during colonization are still with us today. Be that the economic imbalance between the descendants of the plantation owners and those that forcibly toiled on them. The ingrained concepts of superiority and inferiority based on ones origins from Europe, America, or West Africa. The struggle to decolonize society is still a socio-economic project working toward the Human Rights of all citizens in Louisiana.

Since the end of Reconstruction the methodology of the 98% in Louisiana has been the way of Nonviolent Resistance. Be that the efforts of the Comité des Citoyens in the 1890’s that culminated in the historic court case Plessy v Ferguson, or the movement that Louisianian’s participated in that led to the passage of Cilvil Rights Bill in 1964. The evolution of decolonizing Louisiana continues. It’s not enough to have civil rights, the movement must progress to human and economic rights. In this evolution, so must the means evolve to bring these rights about. That evolution is nonviolence…Nonviolent Resistance is a sword that heals. Its aftermath is the creation of a system of peace rooted in equality and justice.

FIN

Yours truly, Eric Gabourel, in front of the Petit Palais in Paris